In working with clients who are applying for a liquor license, or answering the legal questions of those who already one, I am often confronted with the question: “Why would they have a law like that?”, in reference to individual parts of the Connecticut Liquor Control Act. As a lawyer, I will explain that “the law is the law” and, if the person asking the question wants to keep their liquor license, it is in their best interest to follow the law.

In working with clients who are applying for a liquor license, or answering the legal questions of those who already one, I am often confronted with the question: “Why would they have a law like that?”, in reference to individual parts of the Connecticut Liquor Control Act. As a lawyer, I will explain that “the law is the law” and, if the person asking the question wants to keep their liquor license, it is in their best interest to follow the law.

The debate this year in the legislature over amending the Liquor Control Act has given the public a glimpse into provisions of the liquor laws that, depending upon your vantage point, some consider odd: Can package stores sell olives? Why can’t a restaurant owner buy liquor from a package store, but has to do business with a wholesaler? Why don’t more convenience stores sell beer?

While it used to be just clients who would ask me “Why would they have a law like that?”, now I have plenty of average citizens, not previously aware of some aspects of the liquor laws, asking me the same question. As former Commissioner of Consumer Protection and Chairman of the Liquor Control Commission, I am familiar with the background of how certain parts of the Liquor Control Act came into being. I have also had a ringside seat to witness attempts, successful and unsuccessful, to amend the Act.

Among those proposals that got debated during my time at Consumer Protection were the creation of a new liquor license called a wine festival permit, changes to the law to permit viticulture classes at local community colleges, and amendments to the Act to allow direct shipment of wine to consumers after a decision by the United States Supreme Court.

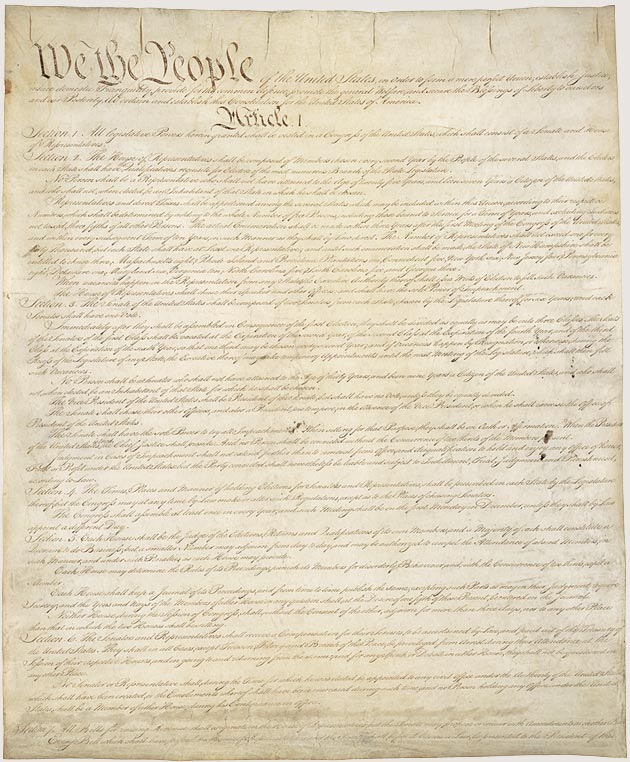

State liquor laws, including those of Connecticut, occupy what a unique area in American law. To those who ask me “Why would they have a law like that?”, I will point out that the sale of alcohol has been the subject of two amendments to the United States Constitution – the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the sale of alcohol, and the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th amendment and returned the issue to the individual states.

You cannot point to another commercial activity that has received similar treatment in American law. The healthcare, insurance, and banking industries, for example, have all been the subject of federal laws, but only the legality of the sale of alcohol merited the amendment of the chief governing document of the American system, the U.S. Constitution – not once, but twice!

I point this out, not necessarily to justify some of the odd provisions in the liquor laws, but rather to place them in a context that almost always is missed. In most cases, things don’t become law by accident; someone sees a problem and they go to their state representative or state senator, who attempts to fix the problem by amending an existing law or creating a new law. When the 21st amendment to the Constitution was ratified, repealing Prohibition, each state then had to enact its own liquor laws, governing how liquor could be sold on a commercial basis, and in 1934 Connecticut enacted the basics of its present liquor licensing laws.

While Prohibition had been repealed, some of the problems that had been the cause for its enactment remained. Both before Prohibition and after, there certainly was the perception that, left to its own devices, the liquor industry would grow too powerful and promote the consumption of alcohol, past a point of enjoyment, to a point where an individual became a danger to themselves and society. To prevent the concentration of too much influence and power, there are a series of provisions in the Liquor Control Act that try to keep the liquor industry decentralized. Limits on who can sell alcohol and how the ownership of a business that sells alcohol is configured are found throughout the Act.

As a result of these provisions in the law, any new application for a liquor license has to be accompanied by documentation that shows who owns the business, where its financing comes from, and if any of the individuals to be involved has a criminal history.

I hear my clients grumble about the level of documentation that sometimes has to be gathered: past bank statements, copies of leases, even lists of kitchen or business equipment. “All this to open a business?”, the client will ask. As I tell my clients “it is what it is – let’s do it right from the beginning, so you don’t have to worry about having a problem later.”

Indeed, I do encounter situations where, seemingly innocently, clients failed to disclose something they should have in the liquor licensing process, and they are at my doorstep because the issue has now “come home to roost.” Sometimes it is the financing of the business by a third party. Someone contributed money at the time the business was created, or somewhere during the course of its existence, and arguably acquired some ownership interest in that business.

On a number of occasions where this has happened, the lawyer who was involved in assisting the client in creating the business entity and applying for the liquor license will say “it never occurred to me that there was a law requiring that kind of disclosure – why would they have a law like that?”

We can debate whether certain provisions within the Liquor Control Act should be abolished or amended. In the meantime, play by the rules. It’s in your best interest to know what the law says and to conduct your business in compliance with those laws. And, sometimes, understanding why a law was passed in the first place, can give insight into why and how it is currently enforced.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Jerry Farrell, Jr. served as Chairman of the Connecticut Liquor Control Commission from 2006 to 2011. An attorney for 19 years, he now practices liquor licensing law and can be reached at jerryfarrell@ctliquorlaw.com. The opinions expressed here are general guidance and should not be taken as specific, individual legal advice. Consult an attorney as to your own specific situation.